Pericarditis

Pericarditis typically causes chest pain, most commonly worsening with taking in a deep breath (pleuritic chest pain), sometimes worsening when lying down and often relieved by sitting up and leaning forward. The chest pain is caused by the inflamed pericardium rubbing against the heart. The pain may radiate to the shoulder, neck or back and is typically sharp and “stabbing.” The chest pain may feel like pain from a heart attack and, thus, if you have chest pain, you should call 9-1-1 right away.

Pericarditis can be caused by an infection, most commonly viral infections although rarely bacterial or fungal infections can be the cause (the most common cause outside of the US is tuberculosis). It can occur due to general inflammation after a heart attack, typically larger heart attacks (Dressler’s syndrome) or after open-heart or chest surgery (post-pericardiotomy syndrome). In up to half of cases it occurs for no discernable cause (idiopathic) but pericarditis can be related to auto-immune (or immunological) inflammatory conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis or be caused by certain medications. Trauma, tumors, cancer and radiation to the chest are also less common causes. Pericarditis can cause shortness of breath and it can be accompanied by fever and fatigue. Infrequently, arrhythmias can occur such as atrial fibrillation.

While antibiotics infrequently are required for non-viral infectious causes, most cases are treated with NSAID’s (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as indomethacin, ibuprofen or naproxen) and sometimes cochicine is added to help decrease the pain and inflammation. In more severe acute cases, steroids sometimes are added. Most patients recover in two to four weeks.

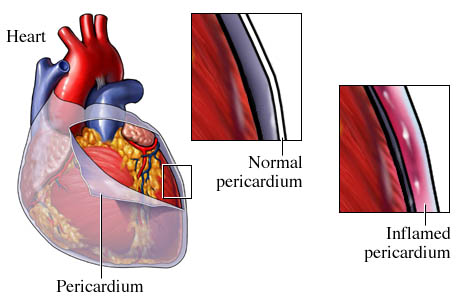

The pericardium normally has two layers, an inner or visceral pericardium lining the heart and an outer parietal pericardium with a very small amount of fluid between the pericardial layers to help prevent friction between the two surfaces and to help cushion the heart. When the pericardium is inflammed, it can leak inflammatory fluid which can build up between the pericardial layers (percardial effusion). Most cases of pericarditis cause minimal fluid build-up and can be monitored with an echocardiogram and will gradually resolve. However, pericardial effusions can grow and if this occurs rapidly or leads to a large pericardial effusion, a significant amount of pressure from the fluid build-up can cause the heart to not be able to fill or beat properly. This can lead to a life-threatening condition known as pericardial tamponade. Pericardial tamponade and sometimes moderate to large pericardial effusions (even without tamponade) require the pericardial effusion to be drained, sometimes very urgently. This is done with a pericardiocentesis where a needle is inserted through the skin of the lower chest and through the pericardium so that fluid can be drained to relieve the pressure around the heart. Sometimes analysis of the fluid removed helps determine the cause.

Usually pericarditis occurs suddenly (acute) but less commonly can be more indolent and persistent (chronic). If the pericarditis is not adequately treated or in other rare instances even with appropriate treatment, the inflammed pericardium does not heal properly and becomes stiff and can stick to the heart. Even without any significant fluid build-up, this prevents the heart muscle from fully expanding in between heart beats and constricts the function of the heart. This is known as constrictive pericarditis but often there is no residual inflammation and is more appropriately referred to as pericardial constriction. This can lead to persistent fatigue and shortness of breath, swelling of the feet, legs and abdomen often with weight gain (heart failure type symptoms). This rarely improves on its own and is notoriously challenging to treat. Surgery to remove the thickened and stiff pericardium (pericardiectomy) and allow the heart to function properly is often considered.

Pericarditis is diagnosed often based on the patient’s history and physican exam where, using a stethoscope, a classic “rub” can be heard from the inflammed pericardial layers rubbing against each other and the heart. Tests used to help confirm the diagnosis include an EKG(electrocardiogram); chest x-ray and echocardiogram. In more severe or chronic cases, cardiac catherization, cardiac CT scans or cardiac MRI can be used. In some cases, it is not clear if someone is having a heart attack or pericarditis so coronary angiography needs to be performed.

Click here for more information on pericarditis.

Updated 01/23/13

Written by and/or reviewed by Mark K. Urman, M.D. and Jeffrey F. Caren, M.D.

PLEASE NOTE: The information above is provided for general informational and educational purposes only and should not be used during any medical emergency. The information provided herein is not intended to be a substitute for medical advice, nor should it be used for the diagnosis or treatment of any medical condition. Accordingly, it should not be relied upon as a substitute for consultation with licensed and qualified health professionals who are familiar with your individual medical needs. Call 911 for all medical emergencies. Links to other sites are provided for information only – they do not constitute endorsements of those other sites. Please see Terms of Use for more information.